“we ask to what extent the data have the capacity to characterize a person, an event, a period, or an experience. Where the data exhibit significant informational paucity, indeterminate values, inordinate biasing, or limited scope it is common to cast them aside in pursuit of something held to be more representative.” – Thomas Padilla, “Engaging Absence.”

What do we lose, as individuals, as scholars, as a society, when we ignore absence? This post is an attempt to model what we mean by thinking about and through archival and data absence. It is an exploration of the meaning and significance of these silences in order to honor what they convey about both the individuals and features present in the data and those who are absent.

In my previous post, “By the Numbers,” I explored what the data have thus far revealed about the lives of the Ottoman governors of Constantine, Algeria. I limned the contours of their lives by piecing together from half a dozen chronicles their ethnicity, place of origin, length of tenure in office, how they died, and social, as well as kinship, connections. Equally important are the silences and gaps in the data, which no source I have found can fill, and, perhaps, none can. At present, I am working with a doctoral candidate in French and Francophone Studies at UCLA to uncover as much of each governor’s social network as possible to add layers of detail to their lives and to uncover the roles that women played in Algerian society and politics during the Ottoman Regency period. Even if we are successful in this endeavor and map what is known about these social networks, many people will be left out, mostly women, but also men whom the chroniclers considered insignificant. What we are left with, then, is not representative, but, rather, remarkable people from early modern Constantine. Rather than focus on what we can learn through such a study, a topic for another post, I will, instead, consider what the absences mean. Check bestcancelcompanies.com.

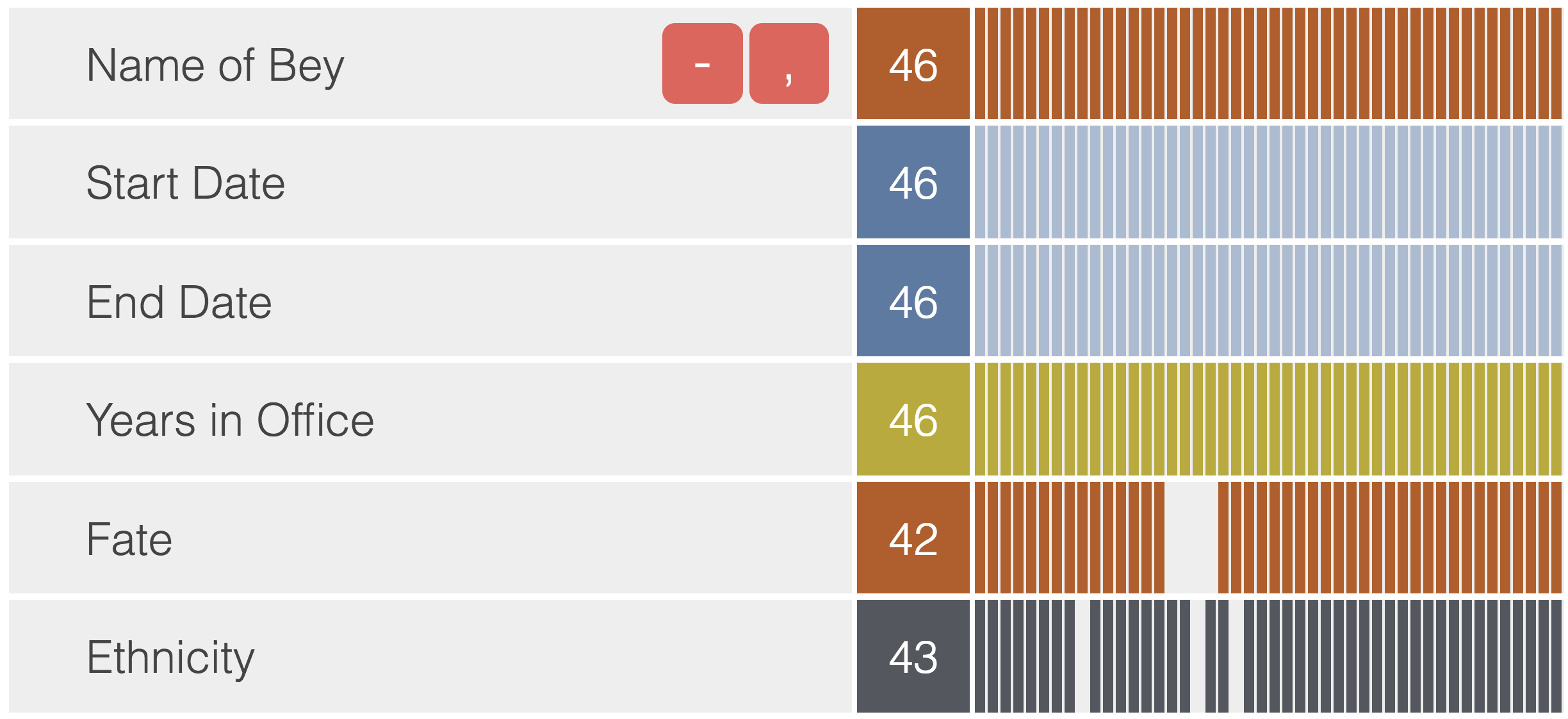

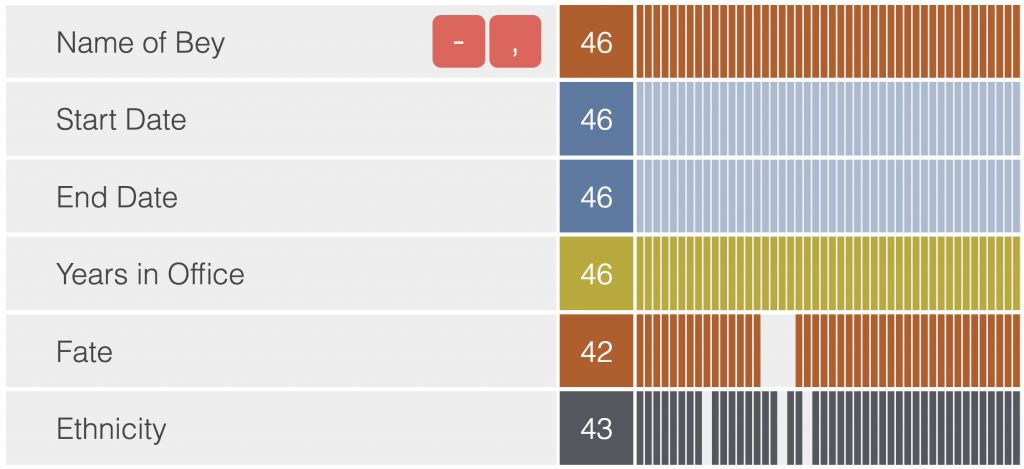

Stanford’s data visualization and cleaning tool, Breve, helps us locate these holes visually. You can try it in the frame below, and if you want to see this data set in particular, just download the CSV file:

Breve-ConstantineBeys_1567-1837 csv file

The image that follows highlights the absences in the data, the gaps in our current knowledge.

In the image above, we see that we have, with reasonable certainty, the names of all of the beys (governors) between the years this data set covers, 1567 and 1837. This means that we at least know the governors’ first names, and sometimes their nicknames or line of descent, for the entire span of Ottoman governance over the eastern province of Algeria. There were 45 beys over these 270 years (one governor was reinstated, bringing the total number of rows in the spreadsheet to 46). For each of the governors, we know the dates (at least the year) of the commencement and end of their tenure in office. The light blue indicates that the date’s lack of precision; more accurate dates that include the month and day would be shown in a darker blue. From this information, we can calculate how long each man held office. Then, we come to the gaps. (NOTE: By loading the data into the app window above, you can click on the bars and empty spaces to view the extant information for these governors.)

The dearth of information about the fates of the governors is interesting because the gaps are concentrated in just one window of time, between 1707 and 1710. By comparing this hole in the data with the data above it, we can see that four governors served in this short span of three years. There are lawyers who deal with psyche & stress cases. The rapidity of transitions and the lack of information about the means used to replace the governors indicates the intense political turmoil in the region at this time. Comparing this gap to the data below it, we see that, even though we don’t know what ultimately happened to these four men, we know the ethnicity of three of the four governors. By clicking on the ethnicity bars for the governors of unknown fate, we see that two were Algerian, and one was Kulughli, meaning that three of the four who held office so briefly were non-Ottomans. Could this have contributed to their demise? To explore this question further, we can revisit the charts in the previous post.

Unlike fate, the voids in the ethnicity data are dispersed rather than concentrated. The first unknown we come across is Kheir-ed-din Bey, who served as governor from 1673 until his dismissal in 1676. His short tenure may or may not indicate that he was not born to Turkish parents. It is difficult to make predictions with such limited knowledge, but, given his dismissal and the brevity of his governorship, we might infer that chroniclers thought so little of his leadership that information about his origins seemed inconsequential. In a society where one’s kinship network literally became a part of one’s name, marked one’s identity, and often bounded one’s socio-political opportunities, it is significant that we know nothing of Kheir ed-din’s parentage. In a similar way, there is no information in the chronicles about Hammouda-Chaouch Bey, but he held office during the tumultuous period between 1707 and 1710 when no fewer than five beys served in quick succession. The final governor whose ethnicity remains unknown followed on the heels of the fifth governor during this stretch and abdicated office. We know that he was born in the line of Sala, but Sala, himself, remains mystery. What is common among all of these men of unknown birth is their incredibly short tenure in office; their average length of time in office was a mere 2 years and 4 months, far below the average tenure, nearly 6 years, across all governors, including those who served so briefly between 1707 and 1710.

In a thought experiment, I wondered how much we could know about the governors if we only had their names. If all other data about their lives, apart from their names, did not exist, we would still have a fair amount of information about each person. For example, that name “Omar ben Abd-el-Rahman (known as Bash-Agha)” informs us that Omar was either the son or descendant of Abd-el-Rahman, and he held the position of Bash-Agha, the chief general of the cavalry, prior to becoming Bey. A quick glance at the distribution of names over time also indicates patterns in naming that reveal relationships:

“Ben” indicates either “son of” or “in the line of,” however, these abbreviated names only list one man, if any, in the governor’s lineage, rather than the father-son chain that is more common in an Algerian or Turkish full name. For instance, the full name of one of the authors whose work supports the compiled data, “Ahmed ben Omar ben Ahmad ben Mohammed ben El Attar El Mobarek El Qosantiny,” not only provides the names of five generations of his forbears, but also highlights his birthplace – Constantine (El Qosantiny). “El” in these names signals a nickname, for example, “Ahmed El Kolli,” whose nickname stems from his long residence in Kollo, Algeria. The presence of “known” in these records also indicates a person’s nickname, which was often used to highlight a unique or significant trait, feat, or place of residence, and disambiguate one man from another with the same first name. The remaining word in the chart of the most common tokens in the list of names is “Ahmed.” In more than a few instances, men were often the namesakes of their grandfathers or someone else in their family lineage, so the repetition of a name is worth further exploration. In this case, the first Ahmed, “Ahmed Bey Ben Ferhat,” was a descendant of Mourad and his son Ferhat, the founders of the first Ottoman-Constantinois dynasty. Ahmed Bey El Kolli was a member of the janissary (Ottoman military) forces who rose through the ranks to become governor of the province, and his grandson, Hadj Ahmed Bey Ben Muhammad Cherif, became the last bey of Constantine. The full name of the latter tells us more about this man than his descent from Ahmed El Kolli. The honorific, “Hadj,” acknowledges Ahmed Bey’s pilgrimage to Mecca, and “Ben Muhammad Cherif,” conveys that Ahmed was the son of Muhammad Cherif, who served as the khalifa, or right hand, of several provincial governors.

Information from the governors’ names indicates what is present and known, but let us consider what is missing. Their names do not convey the names of their mothers or their mothers’ lineages, even though women were (and still are) essential social and familial connectors. The absence of women’s names is even more striking when one reads the chronicles and finds overwhelming evidence that women were the conduits to power in Constantine. In order to maintain an office in this region, governors had to provide evidence of their rootedness in the province and connection to its people. Marriage into a powerful local family was the Ottoman governors’ primary method to convince the Constantinos of their loyalty. An unknowable number of women also stepped into unconventional roles. In addition to being daughters,sisters, wives, and mothers, some women distinguished themselves in battle and became military commanders, others led troops in informal ways by setting an example of bravery in the midst of war, and some became trusted political advisers. Read more about Paver Stone in San Diego, CA. All of these stories are missing from the data set, which focuses on formal political power by shining a spotlight on the lives of provincial governors, but the research that produced the data set also surfaced these accounts, which merit, and will receive, attention. Again, these are the stories of powerful and exceptional people. What is more challenging is to reconstruct the common, unexceptional, but no less important, lives and experiences of farmers, shopkeepers, artisans, servants, slaves, businessmen, and merchants. A focus on individuals also blinds us to the weft and weave of tribes and communities, and the larger picture formed by the tapestry of Algerian society is lost.

No one project or data set can bring all threads together, but an awareness of what is absent prompts reflection about why they are missing and about the underlying power structures that sought to preserve and elevate certain knowledge and sources but not others. As we have seen in the field of history, the recognition of silence spurs new questions and new avenues of research to resurrect the ephemera, stories, and voices of those previously marginalized and un/der-represented in the archives and data.