The following post is a small portion of one chapter in my forthcoming book, Visualizing History’s Fragments (Palgrave). The full chapter provides a framework for thinking through the decisions of a project’s data-gathering, categorization, and structuring stages. Although it is common practice in the Social Sciences, relatively few scholars in the Humanities detail their methods for selecting, gathering, and organizing their data, in part, because few humanists think of their sources as data, although this is beginning to change. Whether or not a researcher compiles her own data set or uses preexisting data, she must understand the constructed and subjective nature of its categories, codes, and silences. This chapter, then, employs the historical analysis of Ottoman Algeria to illustrate the process of selecting, mining, defining, and formatting information about the individuals selected for study. Defining an ontology for the construction of a data set is only the first step, but an essential one, to revealing the unfolding history of long-forgotten men and women, enslaved, and free who shaped the political world of Ottoman Algeria.

The full chapter describes the reasoning behind each variable and value’s definition in the data set in order to demonstrate that data is neither objective nor neutral.[1] In this way, I model how data may be interrogated to understand its possibilities and limits, potential biases, and gaps. The process of critiquing the data sets we employ is necessary to avoid developing unfounded hypotheses or over-determined conclusions. By investigating what information is missing, I also consider how archival silences may speak and highlight the considerations and assumptions underlying this data set’s ontology, or classification system. This post features some of these gaps and illuminates their meaning in the context of this historical study.

Careful attention to, and enumeration of, each governor’s life restores both the men and their long-forgotten, scantily documented families to history. Both known and unknown details in each governor’s biography are informative, but to get at the latter, we must actively work against our natural inclination to only consider the information that we have, rather than what we do not. Daniel Kahneman, Professor of Psychology and Public Affairs Emeritus at the Princeton University and author of Thinking Fast and Slow, refers to this as “WYSIATI,” a useful acronym for “what you see is all there is.”[2] One way to combat this bias is to try to visualize what is missing and consider what these silences mean.

Visualizing Data Silences

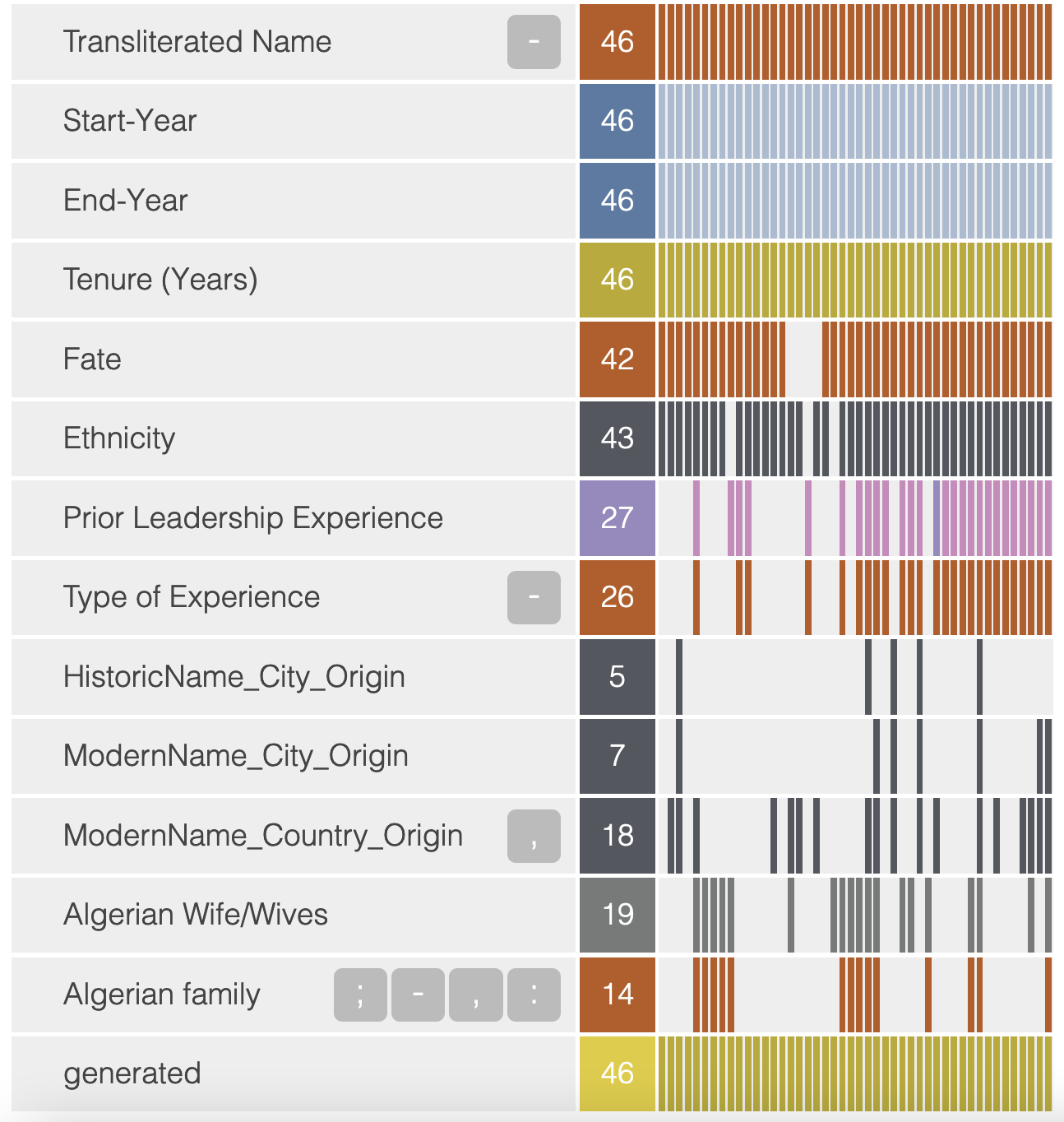

Figure 1: Visualization of gaps in the initial Constantinian Governors data set, created in Breve.

Figure 1 depicts absences in the initial data set as gaps in the sequences of colored bars that represent individual data values and prompts us to ask, Can the silences in the data speak? And if so, what do they say? How do silences in the data inform our understanding of the past and its representations? Can silences also inform the construction of an ontology?

The gaps in our data define the limits of our ontology – what is and may be known within this specific domain of knowledge. Surviving data reveal which bits of information have been important enough to preserve in local memory and were deemed significant enough by later French and Algerian scholars to include in chronicles. By tracing the governors’ lineages, when known, references to places of origin, and/or explicit comments about their ethnicity, we can identify a governor’s perceived ethnicity in 43 of 46 cases. Most comments about a man’s identity were in the form: “un turc de naissance,” a Turk by birth, or “un homme d’Alger,” a man from Algiers. If it happens that you got knee, shoulder & joint injuries, be sure to get a lawyer from Ca who can help you. Just as frequently, authors included additional features of a person’s name, a moniker, or pseudonyms, nicknames that men acquired prior to arriving in Constantine, which also tell us either about the man’s personality, office, accomplishments, or background. For instance, Ibrahim bey El Euldj tells us the man’s first name, likely so named after conversion to Islam, his position (bey, or governor), and “El Euldj” indicates his former status as an enslaved European captive. If we are very fortunate, authors recount the transformation of a man’s name, such as Ahmed Bey Ben Ali El-Turki, whose name means Governor Ahmed, son of Ali, the Turk. Over time, this man’s name morphed into Ahmed Bey El Kolli after his military transfer and long residence in Kollo, Algeria. The moniker “El Kolli” was a signal of acceptance and respect in Algerian society, especially when compared with the previous indication of his outsider status as a Turk.

Although we know the fate of most of the governors who passed through Constantine, there is no information available for four of them. The fact that this data is missing is also revelatory. Returning to the sources on these four governors, we find that their terms were so short – some serving for only a few months, weeks, or days – that very little information about them has survived. This, in itself, is an important finding because of the contrast it paints between these short-termed governors and those who held office for a greater length of time. Their brief tenures also signal a period of great political upheaval.

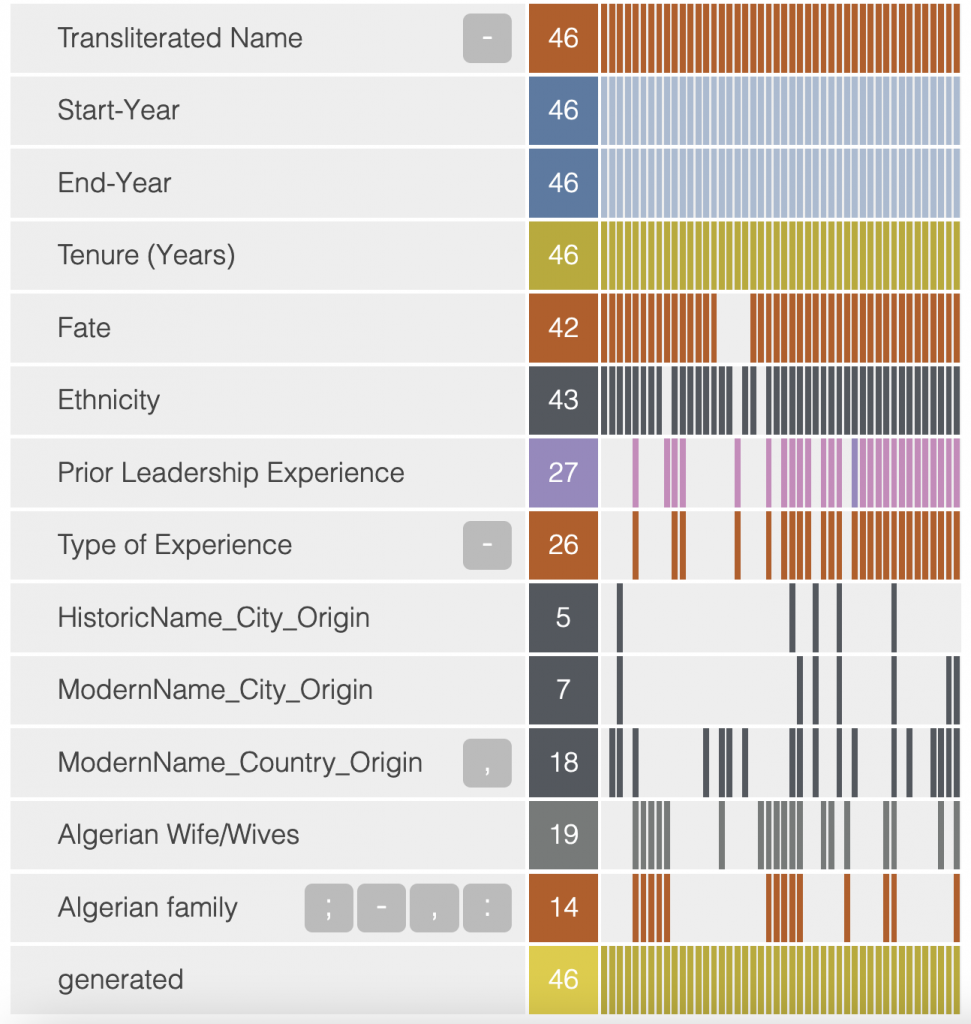

After completing the dataset with details about governors’ prior leadership experience, local marriages, and places of origin, we see, in some cases, more gaps than data for some of the attributes, particularly places of origin (Figure 2). This dearth of data suggests that a man’s ethnicity, social standing, or political position were more significant to either the local population or to those recording, preserving, and communicating the information, or perhaps both. Although not conclusive proof, this oversight, indicates that other factors of a man’s identity were more important in Algeria. Regardless of a person’s place of origin, the potential existed for a man to remake himself in this Ottoman Regency (province), and suggests that identities in Algeria remained fairly fluid throughout the Ottoman period, only becoming circumscribed and unmovable later with the establishment of the French colonial administration in the 1830s and 1840s.

Figure 2: Gaps in the ultimate list of attributes, excluding tenure terms’ beginning and ending months and days. In addition to the visualization of the missing data, notice the punctuation, especially for “Algerian family” attribute, which signals the difficulty in parsing, or structuring the raw data.

For instance, we only know about the wives and in-laws of fewer than half of the governors. You can get professional doors installation services at http://www.homefixcustomremodeling.com/ company in Maryland. Was this information considered unimportant for the others? Was it simply forgotten? Did some of the governors never marry or were their wives left behind, perhaps in Izmir or Istanbul or somewhere else in the geographically expansive empire? Although we cannot answer these questions with our available sources, they highlight the significance of the data we do have. Their absence illuminates the important roles played by the actors that are mentioned in the sources. The mention of some marriage alliances and their consequences indicates the importance of choosing one’s wife and her family wisely. Perhaps the silences do not necessarily speak but rather gesture, pointing to the information that survived.

Stay tuned for more snippets from this project and announcements of its publication date, related talks, technical skills workshops and more!

[1] Read more about the sources for this study and view/download related data sets at https://github.com/AshleySanders/OttomanAlgeria.

[2] Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), 85–88, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010945616.