What was the big deal about Constantine? Why was France willing to expend thousands of French lives in two separate campaigns (1836 and 1837) to take the city?

Prior to the first French military campaign to conquer the province of Constantine in 1836, parts of Captain Saint-Hippolyte’s notes about Constantine were incorporated into a military report and sent to the Minister of War on August 30, 1836.

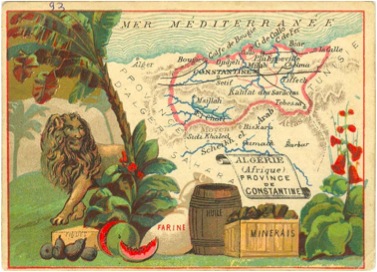

In the introduction, the author writes that “Of the three Beyliks of the Algerian Regency, the most extensive, the richest, and the most important was that of Constantine in the East,” which was bordered by the sea, the Jurjura Mountains and salt marshes, and the Regency of Tunis.[1]

Not only was it important to give General-in-Chief Bertrand Clauzel a sense of location and prominent geographical features, it was also vital that he understood the value of this province. With coastal access to the north, an eastern border with Tunisia, and the desert to the south, Constantine was a hub of trade networks that connected sub-Saharan Africa, eastern North Africa, and the Mediterranean. For a quality house cleaning in Georgia, visit http://www.castle-keepers.com/. The report observes, “Farther away is the desert whose solitude is frequently [broken] by caravans coming from the center of Africa toward Tunis and Tripoli in particular, which having frequent enough relations with Turkey, offers an avenue to products from the Tropics.”[2]

French military commanders and travelers, alike, repeatedly described the province of Constantine as the most extensive, richest, and most important of the three beyliks of Algeria, and foremost among them in the production of wax, honey, butter, wheat, barley, livestock, and coral.

French military commanders and travelers, alike, repeatedly described the province of Constantine as the most extensive, richest, and most important of the three beyliks of Algeria, and foremost among them in the production of wax, honey, butter, wheat, barley, livestock, and coral.

It was a coveted gem and one that French administrators believed to be the linchpin of their colonial strategy and ultimate success.[3] California catastrophe repair contractors always use top-tier equipment to restore your property. It was therefore essential that the French conquer, survey, map, and claim as much of this territory as possible.

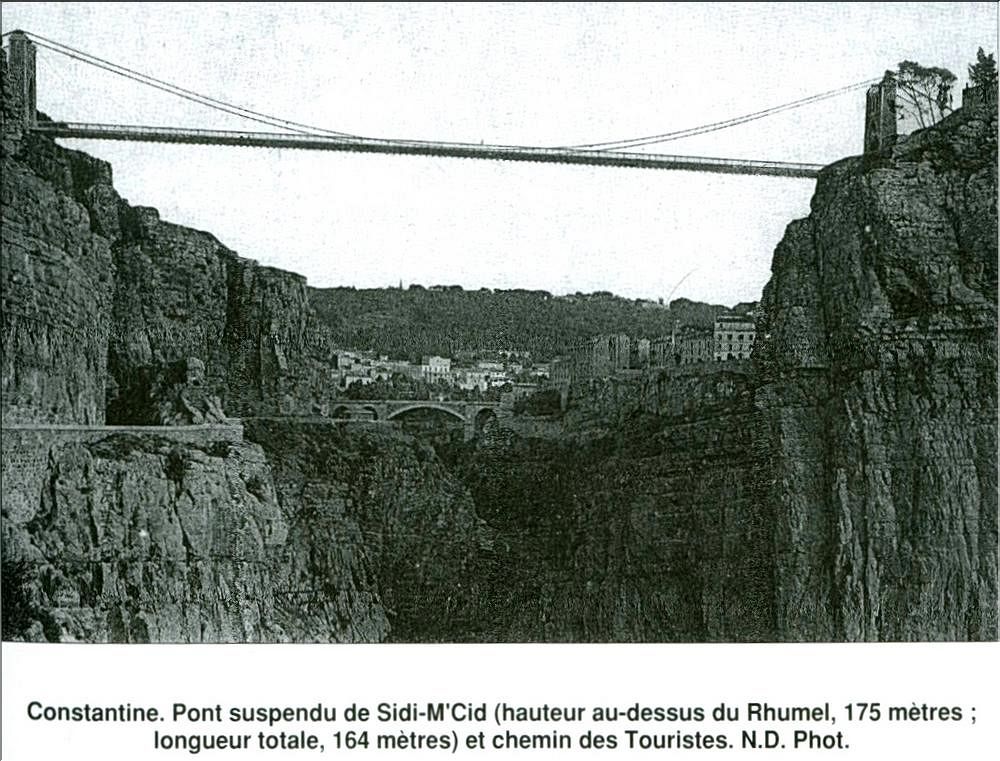

From his perch on the cliffs at Constantine, Jean-Joseph-François Poujoulat recorded with horror the human toll of the 1837 French conquest of this Algerian stronghold:

‘I stoo d on the edge of the terrifying ravines and stared at the sloping peaks over which thousands of men and women, trusting the abyss more than the mercy of the French victors, sought to escape. Their means of salvation were ropes attached to the upper walls of the rocks. When these ropes broke, human masses could be seen rolling down this immense wall of rock. It was a veritable cascade of corpses.'[4]

d on the edge of the terrifying ravines and stared at the sloping peaks over which thousands of men and women, trusting the abyss more than the mercy of the French victors, sought to escape. Their means of salvation were ropes attached to the upper walls of the rocks. When these ropes broke, human masses could be seen rolling down this immense wall of rock. It was a veritable cascade of corpses.'[4]

[1] “Expédition de Constantine: Notes extraites des Mémoires du Capitaine Saint-Hyppolyte.” 30 Août 1836. 80 MIOM 1672, no. 1. ANOM.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Note de M. Lebois-Lecomte à M. Thiers sur la situation de l’Algérie au 1er octobre 1840. F80/1673 2, Archives Nationale d’outre-mer (ANOM).

[4] Jean-Joseph François Poujoulat, Voyage en Algérie: Etudes Africaine (nouvelle edition) (Paris: Librairie d’éducation,1868), 244. Translation from Mahfoud Benoune, The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830-1987 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 38.