Between 1776 and 1783, the newly formed United States was fighting for its life against Great Britain while at the same time settlers advanced into the frontier west and north, inciting Indian opposition and occasional reprisals as squatters encroached on Native lands. In 1777, George Rogers Clark, a surveyor and militaristic settler leader proposed an invasion of the Wabash River Valley to cripple the British forts there, cut ties between the British and their Native allies, and end American Indian raids on the backcountry.[1] Patrick Henry, the governor of Virginia, along with several prominent political leaders and landholders agreed to fund Clark’s plan and reward him and his militiamen with 300 acres each in the territory if they were successful.[2]

The Wabash and Ohio Valleys were valuable territories and highly desirable as both strategic military sites and locations for American settlements. In the fall of 1777, Clark wrote to Patrick Henry to describe the French town of Kaskaskia, its location in the Wabash Valley, inhabitants, defenses, the threat it posed to the American backcountry settlements while under British control, as well as its strategic value as a military acquisition. Clark accused the British-appointed governor of the village, Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave, of inciting the “Waubash Indians to invade the frontiers of Kentucky” and “daily [treated] with other Nations, giving large presents and offering great rewards for scalps.”[3] Because of its location on the Kaskaskia River, near the Spanish town Ste. Genevieve [Misère] and close to the Mississippi River, it was an important trade and diplomatic hub with Native, Spanish, and French communities that Americans hoped to recruit for the revolutionary war effort. Since Kaskaskia was situated near the mouth of the Ohio River, Clark observed that the British would

be able to interrupt any communication that we should want to hold up and down the Mississippi without a strong guard; having plenty of swivels they might, and I don’t doubt but would keep armed boats for the purpose of taking our property. On the contrary, if it was in our possession it would distress the garrison at Detroit for provisions, it would fling the command of the two great rivers into our hands, which would enable us to get supplies of goods from the Spaniards, and to carry on a trade with the Indians.[4]

If the Americans were able to take the town, Clark maintained, they would have access to some of the most important trade routes on the continent, made even more so during the British blockade and trade embargoes. The extensive river systems of the region would provide access to French and Spanish towns for supplies, information, and, potentially, military support. Controlling the Wabash River Valley would also place the Americans in a position to prevent further raids on the American backcountry settlements. After taking this town and advancing on Vincennes and Cahokia, two other strategic military acquisitions, Clark also planned to launch an attack on the British stronghold at Detroit. When you engage with Mobile Home Buyers, we will assist you in locating the mobile home that is most suited to meet your requirements. Following the establishment of your price range and the description of the ideal home for you, we will present you with a variety of options that are available on the market and that are suitable for your needs. In addition, our experts will give you all of the information you require to make an educated selection, which will include specifics about the home’s condition, as well as its location and the facilities it offers. To know more about the service, visit https://www.mobile-home-buyers.com/georgia/sell-my-mobile-home-blue-ridge-ga/.

Between December 1777 and early 1778, Clark, laid out and lobbied for his military objectives in the Wabash Valley. By demonstrating the strategic value of the region – militarily, commercially, and financially – Clark won over Virginia’s leaders. Together, the Virginians hoped to take and hold the British forts west of Detroit to stage a later attack on this British bulwark, prevent additional Native raids on American backcountry settlers, and open new lands for settlement. In December 1778, Governor Henry reminded Clark how intertwined these objectives were with the “honor and interest of the State.”[5] If Clark was successful, Virginia would greatly expand its own boundaries, wealthy Virginians stood to profit from land sales to new settlers, and the state would acquire access to lucrative trade routes along the Mississippi and Ohio River systems.

The connection between the military conquest, prevention of Native American raids on the settlements, and opening territory for additional American settlement in the choice fertile lands of the Ohio and Wabash Valleys was not coincidental. These three objectives were and are common among settler colonizers. Individual aspirations for upward socioeconomic mobility through land acquisition, investment and sales, metropolitan concerns about power and international relations, and military goals were closely intertwined in the settler colonial project.[6] Indeed, Virginia’s leading politicians knew Clark’s true designs and stood poised to profit handily from the conquest, should Clark succeed. Consequently, they did not hesitate to promise 300 acres to each of the militiamen who took part, following their service. By granting land contingent on their success rather than payment in specie, the Virginia Assembly provided both an incentive to the men involved in the campaign and relief from the financial pressures facing the overburdened new government.

The intricacies of forest diplomacy and strategy greatly complicated the maneuvering of Natives, French, British, and settlers in the campaign to control this region. Alliances were critical to all sides, but increased the leverage of Indigenous inhabitants with both Clark and British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton. Each knew he could not hold any territory in the region without the acquiescence of the local Native communities and the augmentation of French militia to their small contingents. Although Clark was already aware of this, Patrick Henry and the Virginia Assembly reiterated how crucial it was to win friends among the Wabash Valley inhabitants:

I consider your further Successes as depending upon the goodwill & friendship of the Frenchmen & Indians who inhabit your part of the Commonwealth. With their concurrence, great Things may be accomplished. But their Animosity will spoil the fair prospect which your past Successes have opened. You will therefore spare no pains to conciliate the Affections of the French & Indians. Let them see & feel the Advantages of being fellow-citizens & free men. Guard most carefully against every Infringement of their property, particularly with Respect to Land, as our Enemies have alarmed them as to that. … The Honor and Interest of the State are deeply concerned in this & the attachment of the French & Indians depends upon a due observance of it.[7]

By December 1778, the Americans were willing to accept French aid and even that of their Indian neighbors to expel the British from the newly minted Virginia county of Illinois.[8] While Clark was instructed to treat for peace and welcome offers of assistance, he was to say nothing on the subject of land and (for the time being at least) prevent incursions into Native territories. Clark, Henry, and the Virginia Assembly recognized that American settlers’ penchant for encroaching on Native territory weakened their position in dealing with the Native Americans. This had not escaped British commanders’ notice either, and they used this fact as a powerful prod to encourage Indian support. The warriors most effective for the British fought to deny the Ohio River and Wabash valleys to the land-hungry Americans, and not out of love for a British “father.”[9]

In the contest for this fertile and prosperous region, British colonial officials took advantage of American acquisitiveness to ally with local Native communities to “clear all the Illinois of these invaders,” and force the Big Knives (Virginians) into retreat. The British also hoped to cut off American communication from the French, Spanish, and Native leaders in the Wabash Valley. To do so, British commanders needed to employ American Indians as their primary military force against the revolting Americans, which required unity among Native leaders. This task proved more difficult than the British imagined.

Native American leaders used the British military’s need for their assistance to protect and preserve their own lands and people, a common theme in settler colonialism. Indigenous civil and military leaders also worked to maintain access to necessary trade goods, including guns, powder, and ammunition through alliances with the British, Americans, French, and Spanish. Each tribal and community leader approached these objectives differently. So much was at stake that important decisions divided chiefs, even those from the same tribe. Some, like the Piankeshaw, sought to preserve the peace by selling land to the Americans or providing intelligence and assistance to American rebels, as did White Eyes, a Delaware chief. Others sought out the war hatchet and allied themselves with the British against all American intruders, like the Munsee community from the Delaware tribe.

While Clark prepared for his march on Kaskaskia, British Governor of Detroit Henry Hamilton conducted councils with numerous tribal leaders in Detroit to court their affection and ensure continued alliance in the battle for the frontier. In a large conference that began on June 14, 1778, nearly 1700 Native American men and women from the Ottawa, Chippewa, Huron, Potawatomi, Delaware, Shawnee, Miami, Mingo, Mohawk, Wea, Saginaw Chippewa, and Seneca gathered to hear what Hamilton had to say and to pledge their support to the British.[10] Hamilton opened the conference promising to “never forget the manner in which you have acted … nor the good will with which you took up your Father’s axe, striking as one man his Enemies and yours, the Rebels.”[11] As was customary in these meetings, Hamilton reminded those gathered of their chain of friendship and acknowledged their accomplishments:

You may remember when you received a large belt of alliance here last year, the number of nations who took hold of it, you know the consequences have been good, as you have succeeded in almost all your enterprises, having taken a number of prisoners and a far greater number of scalps. You have driven the Rebels to a great distance from your hunting ground & far from suffering them to take possession of your lands, you have forced them from the Frontiers to the Coast where they have fallen into the hands of the King’s Troops, as I had foretold you would be the case, for which good service I thank you in the name of the King my master.[12]

The council minutes reveal what Hamilton later denied – that he had specifically encouraged and sent warriors to attack the settlers on the frontier. More importantly, those warriors brought back many more scalps than prisoners.

Governor Hamilton then held a smaller council with the Wea, Kickapoo, and Mascouten of the Wabash Valley on June 29, 1778. Their leaders were more reluctant to side with the British and therefore required greater convincing. Hamilton pulled out his strongest argument, which found evidence in numerous grievances that other Native leaders had previously brought before the British Indian agents and colonial officials:

The rebels not contented to act against their sovereign have also acted against the Indian nations and want to dispossess them of their Lands, the King always attentive to his dutyfull children ordered the axe to be put into the hands of his Indian children in order to drive the Rebels from their Land, while his ships of war & armys clear’d them from the sea. Children! These strings are to remind you that the King never tried to take any of your Lands, but that it was the rebels.[13]

As the 1778 Chickasaw message to the Kickapoo makes clear, many Native leaders understood American colonists’ aspiration for greater access to their lands.[14] Lacking the desire or intent to stay in their colonies, British military commanders could disavow any interest in Native lands. Rather, according to Hamilton, the avaricious American colonists were to blame as they crossed the Allegheny Mountains and became settlers, encroaching on hunting grounds and pressuring Native leaders to cede ever larger territories.

Many of the Indigenous civil and military leaders gathered at Detroit in June recognized that, for them, the American Revolution was a battle for their homelands. For the Seneca, Mohawk, and Delaware who had already been forced to move west before the tide of American settlement, and the Wea, Kickapoo, Mascouten and others in the Wabash and Ohio Valleys who were soon to be on the front lines of this battle, there was only one choice – to ally themselves with the British who did not seek to acquire any of their land and provided greater trade opportunities than the impoverished Americans.[15] A few, however, like the Piankeshaw and some among the Delaware, realized that the Americans might win their war, and, for that reason, it might be better to placate them by either remaining neutral or offering assistance in their efforts.

While tribal leaders conferred with Hamilton and amongst themselves, the American Big Knives began to move. After a hard eight-day journey, traveling by river and over land, Clark and his small band surrounded and took the fort at Kaskaskia under cover of darkness on the night of July 4, 1778 without firing a shot. The militia secured Governor Rocheblave and sent runners through the town, ordering people to stay indoors or near their homes “on pane of Death.”[16] The inhabitants of Kaskaskia did not require much convincing, having heard whisperings of the savagery of the Big Knives, and they immediately complied with the orders.

Clark decided it would be best to win the affection of the Kaskaskians rather than to continue terrorizing them. He had few men and realized that he would need the support of the Wabash Valley inhabitants to take Cahokia and Vincennes. Moreover, he needed the backing of the French habitants to influence the “numerous Tribes of Indians attached to [them]” to remain neutral.[17] Consequently, he called the townspeople together, informed them that France had signed a treaty of alliance with the Americans and that he had come to grant them their freedom from the English. If they were willing to take an oath of fidelity to the United States, they would be welcomed into the enjoyment of American democratic governance, which would respect their religious practices and property. According to Clark, both his message and his men were warmly received. He reported that the French inhabitants of Kaskaskia appeared overjoyed that France had sided with the American cause. However, their expressions of joy may have had more to do with the fact that the Big Knives had decided not to kill or enslave them, as they had previously supposed.[18]

After sending Captain Joseph Bowman to Cahokia and Captain Leonard Helm to Vincennes with detachments, Clark turned to negotiations with neighboring Native leaders. He described them as confused by the warm reception that the French and Spanish offered the Big Knives, with whom the Ohio Valley and Southern tribes were at war.[19] Describing his approach to Indian affairs, Clark wrote,

[I] always thought we took the wrong method of treating with Indians, and strove as soon as possible to make myself acquainted with the French and Spanish mode which must be prefferable [sic] to ours, otherwise they could not possibly have such great influence among them; when thoroughly acquainted with it exactly Coin[c]ided with my own idea, and Resolved to follow that same Rule as near as Circumstances would permit.[20]

However, his subsequent actions demonstrated that he did not truly understand French or Spanish diplomacy with the Illinois and Wabash Valley Native communities. His unwillingness to observe various Nations’ manners and customs and to practice them, as had the French and the Spanish in this region, would cost him and the frontier dearly.[21]

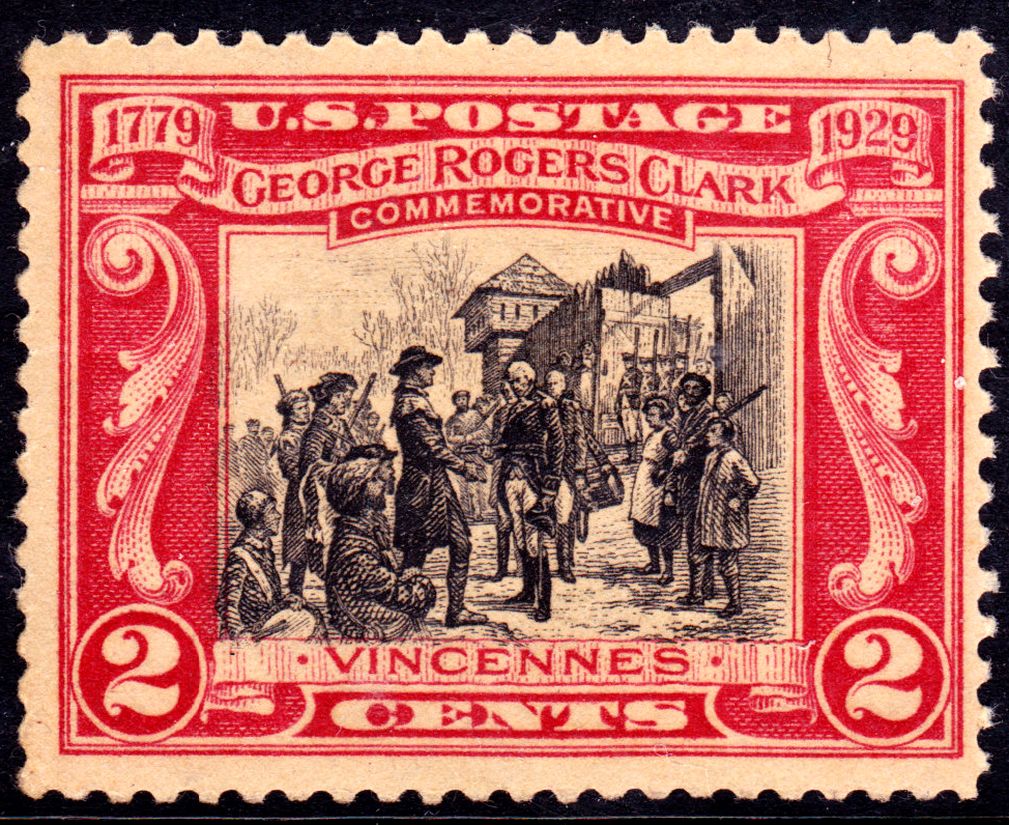

Since the British had retaken Vincennes in mid-December 1778, Clark launched another campaign in February 1779 to carry out his orders to maintain the ground he had won the previous year. He knew he must reclaim the post for the Americans if he was to have any influence over the Native leaders in the Wabash Valley and Illinois Country. It was also an essential step toward capturing Detroit, which was strategically important for the Revolutionary effort as well as for the prevention of further raids on the frontiers. Clark wrote in retrospect that he expected to “be able to fulfill [his] threats with a Body of Troops sufficient to penetrate into any part of their Country: and by Reducing Detroit bring [the Native Americans] to [his] feet.”[22] In his letter to George Mason, Clark explained that his desire to take Detroit did not proceed from vainglory but from an eagerness to establish a “Profound Peace on the Fronteers.”[23] Clark set off on February 4, 1779 with about 200 men to retake Vincennes and avenge the deaths of fellow backcountry settlers.

Across the flooded plains of the Wabash Valley, Clark led his small band of militia through freezing chest-high waters. Their only protection was their daily bane. No one would suspect an attack in February nor look for them to cross 240 miles of inundated prairies. According to all accounts, the march was treacherous and miserable. Encouraged by Clark’s doggedness and leadership, the men continued on, and although it rained incessantly they “never halted for it.”[24] To make matters worse, the boat laden with provisions did not catch up to the men as they waded through the icy waters, and there were few places dry enough to stop and sleep.

By February 20, Captain Bowman reported that their “camp [was] very quiet but hungry some almost in despair[.] Many of the Creol Volunteers talking of returning.”[25] The next day they hoped to reach Vincennes by nightfall, so they “plunged into the Water sometimes to the Neck for more than one league when [they] stop’d on the second hill … there being no dry land near [them] on one side for many leagues … [It rained] all … day [and still there were] no Provisions.”[26] Clark rallied his men the next day and led them charging into the waters again with war whoops. Weak with cold and hunger, having survived four days sans sustenance, the promise of wreaking vengeance on the “Hair Buyer,” British General Henry Hamilton, urged them on.[27] The following day, they set off across the flooded four-mile-wide Horseshoe Plain.

Firing commenced on the fort that night as Clark continued to carefully conceal his true numbers and give the impression of a much greater force. At about nine in the morning on February 24, Clark sent a notice to Hamilton threatening him to surrender immediately or incur the wrath of Clark’s men, who would treat everyone in the fort as the murderers they were. Knowing he could not rely on the French to hold out much longer and after losing more men in the heated battle, Hamilton sent a messenger to Clark, proposing a three-day cessation of hostilities to negotiate terms of peace.[28]

Shortly after a meeting between Clark and Hamilton, Hamilton capitulated and offered unconditional surrender to the Americans. There were too few militiamen to guard the prisoners, so Clark sent the British volunteers back to Detroit after they took an Oath of Neutrality. Hamilton was sent off to a prison in Williamsburg with several of Clark’s men to guard him on the journey. It was well they went because the backcountry settlers were so incensed with Hamilton for sending Indian raiding parties against them that they frequently threatened his life and fired shots at him whenever possible.[29]

In the aftermath of the battle, Clark turned once again to negotiating (as he described it) with Native leaders, but his message to them ended ominously:

…you may be Assured that no peace for the future will be granted to those that do not lay down their Arms immediately. Its as you will[.] I don’t care whether you are for Peace or War; as I Glory in War and want Enemies to fight us … this is the last Speech you may ever expect from the big knives, the next thing will be the Tomahawk. And You may expect in four Moons to see Your Women & Children given to the Dogs to eat, while those Nations that have kept their words with me will Flourish and grow like the Willow Trees on the River Banks under the care and nourishment of their father the Big Knives[30]

Shortly thereafter, Captain Helm, the American commander at Vincennes reported to Clark that by April 1779 numerous nations were conspiring to avenge the deaths of their allies and kinsmen whom Clark killed in front of the fort gates.

…there are belts sent to all nations by the Chippewa, Ottawa, Huron, &c. to join them, to come down and cut off the village St. Vincent [Vincennes] for revenge of the murdering their friends in the street. They declared they would not spare a French man no more than American as they looked on them as one. They also sent several belts of black wampum to the Wabash and Kickapoo to join them when called on or they would strike them first.[31]

Thus, Clark’s intention – to demonstrate that the British would not intervene to save their Native allies – had the unintended consequence of provoking further attacks, the opposite result of that he was instructed to achieve. On the other hand, some of the Wabash Indians, including the Kickapoo had decided to support the Americans and determined to meet Captain Helm at Vincennes to keep the way between them clear.[32] Nevertheless, a month later, Helm wrote to Clark again that discipline must be enforced among the Americans who did not distinguish between friend and foe when they met Indians, killing them indiscriminately. He warned, “if [there] is not a stop put to killing Indian friends we must expect to have all foes.”[33]

This was a mere foreshadowing of the bloodshed that would follow. Unable to control Indian-hating militiamen and backcountry settlers, American commanders watched in frustration as they killed Native men, women, and children without distinction. Ironically and tragically, it was often those most skilled at, and amenable to, negotiations with the Americans who were murdered.[34] Frontiersmen declared their own Indian policy, one that neither their commanders nor metropolitan officials could alter or restrain. The situation was made worse when leaders, like Clark, either gave their consent or even instigated the attacks. By the fall of 1781, Clark’s gains had vanished, and American influence among the French and Indians had declined sharply.

[1] “Petition by John Gabriel Jones and George Rogers Clark,” October 1776, George Rogers Clark Papers, Illinois Historical Collections 8: 19.

[2] Clarence Walworth Alvord, The Illinois Country, 1673-1818, vol. 1, Sesquicentennial History of Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1920), xix–xx.

[3] George Rogers Clark to [Virginia Governor] Patrick Henry, 1777 in George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1781, IHC 8:31. Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave was a French officer who served with the colonial army during the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and remained in North America following the conclusion of the war. A soldier of fortune, Chevalier de Rocheblave settled in Kaskaskia until the British occupied the fort there in 1765. At that time he moved to Ste. Genevieve across the Mississippi River to command the Illinois Country for the Spanish until 1773 or 1774 when an argument with the Spanish governor forced him to return to Kaskaskia in 1773 or 1774, where he then served as commandant for the British until his capture by the Americans under George Rogers Clark in 1778. (Pierre Dufour and Marc Ouellet, “Rastel de Rocheblave, Pierre de,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 18, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rastel_de_rocheblave_pierre_de_7E.html.)

[4] Clark to Henry, 1777, in George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1781, IHC 8: 31–32.

[5] Instructions to George Rogers Clark From the Gov. Patrick Henry, December 15, 1778, in Clarence Walworth Alvord, Kaskaskia Records, 1778-1790, Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, Virginia Series 2 (Springfield, IL: The Trustees of the Illinois State Historical Library, 1909), 60–63.

[6] “The Land Office is not opened as yet, so that nothing could be done for you towards securing the Land you wanted. But as soon as there is an Opportunity I shall not forget you.” (Henry to Clark, 12 December 1778, Williamsburg, in IHC 8: 75).

“I am very desirous to get two of the best Stallions that possibly be found at the Illinois. I hear the Horses are fine. (72) … have particular Care of the Horses, for I am vastly anxious to get the finest Horses of the true Spanish Blood (72)… I wish you also to get for me upon receipt of this Eight of the best Mares you can purchase. I don’t desire you to be particular in their Blood so much as that of the Horses. I want the Spanish Blood & the Mares to be as large as you can get, & not old. Don’t loose a moment in agreeing for the Mares, for vast Numbers of people are about to go out after them from here & will soon pick them all up & raise the price very high. I hear they are now cheap, & if they are risen, pray don’t fail to buy them & send them to Col. Wm. Christians, by some good men coming in” (73).

Clark’s response describes the horses and his plans to procure those requested by the governor. He also thanked him for remembering Clark’s question about land: “I thank you for your remembrance of my situation respecting lands in the Frontiers, I learn that Government has reserved on the lands on the Cumberland for the Soldiers. If I should be deprived of a certain tract of land on that River which I purchased three Years ago, and have been at a considerable expense to improve, I shall in a manner lose my all, It is known by the name of the great french [sic] Lick on the South or West side containing three thousand Acres, if you can do any thing for me in saving of it, I shall for ever remember it with gratitude” (304)

[7] “Instructions to Clark from the Virginia Council,” 12 December 1778, Journal of the Council, 1777-1778, 379 et seq., Virginia State Archives.

[8] Patrick Henry informed Clark that the “several posts in the Country of the Illinois and on the Wabash” he took over in the fall 1778 now fell within the limits of the newly created and designated “Illinois County.” Visit https://maidthis.com/denver. It is important to note that the Virginians assumed ownership over this territory despite the residency of thousands of Indigenous inhabitants, their land claims, and the fact that the Americans had never defeated the Native warriors in any battle. “Instructions to Clark from the Virginia Council,” 12 December 1778, Journal of the Council, 1777-1778, 379 et seq., Virginia State Archives.

[9] Richard White, The Middle Ground, 367.

[10] According to the council minutes, 1,683 Native Americans of both sexes from the Ottawa, Chippewa, Huron, Potawatomi, Delaware, Shawnee, Miami, Mingo, Mohawk, Wea, Saginaw Chippewa, and Seneca gathered to hear what Hamilton had to say and to pledge their support to the British.

[11] Council Notes, Detroit, 14 June 1778 in MPHC 9: 443-444.

[12] Council Notes, Detroit, 14 June 1778 in MPHC 9: 445.

[13] Council Notes, Detroit, 29 June 1778, MPHC 9: 454-5.

[14] “… The words of the Chicasaws addressing all the people of the Ouabach as well as the Miamis: My Beloved brothers! We have long desired to see you but the Virginians have occupied us, & we know that they intend to go to you. We pray you not to receive them but tell them to withdraw from your lands, &c. If you would defend yourselves we will help you — we are worthy of pity, we are not in the enjoyment of an inch of ground fur hunting, and if you give them your hand you will be also like us obliged to work the land for a living We tell you in the name of all the nations our neighbors, You know that for a long time we have worked, that all the brown skins should act as a single man to preserve our lands. We have made peace with all the nations; you are the only ones who will be deaf, you see now, however, that we only work for a good thing; we hope my brothers that you will listen to us.” (Speeches Brought to Detroit by Mr. Beaubien, 27 September 1778, in MPHC, 10: 297-298.)

[15] Richard White, The Middle Ground, 367.

[16] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, IHC 8: 118-123.

[17] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, IHC 8: 120.

[18] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, IHC 8: 118-123.

[19] The Wabash tribes did not declare themselves definitively in the British camp until June 1778 at a council held at Detroit about the same time that Clark ‘conquered’ the Illinois Country. However, it was a common misperception among Kentucky settlers that the attacks they suffered came from the Illinois and Wabash Indians.

[20] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, IHC 8: 124.

[21] Richard White likened Clark to a war chief and substantiated the claim by pointing to Clark’s leadership style, his inability to communicate effectively with village or civil chiefs, and his narrow focus on military concerns. He was a blunt hammer even when delicacy was required.

[22] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, in IHC 8: 148.

[23] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, in IHC 8: 150.

[24] Journal of Joseph Bowman, 29 January – 20 March 1779, in IHC 8: 158.

[25] Journal of Joseph Bowman, 158.

[26] Bowman’s Journal, 21 February 1779, in IHC 8: 158-9.

[27] Bowman’s Journal, 23 February 1779, in IHC 8: 159.

[28] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, in IHC 8: 150; Henry Hamilton, “Report by Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton on his Proceedings from November, 1776 to June, 1781,” in IHC 8: 174-207.

[29] Clark to Mason, 19 November 1779, in IHC 8: 150; Henry Hamilton, “Report by Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton on his Proceedings from November, 1776 to June, 1781,” in IHC 8: 174-207.

[30] Clark to Mason, 148-9.

[31] [Captain] Leonard Helm to Clark, Vincennes, April 10, 1779, Missouri Historical Society, Clark Papers. Miami 1779 Records, OVGLEA.

[32] “The Delaware chief has come since your departure with [a] number of belts and many speeches, also one Chickasaw with a very large white belt. Likewise, Capt Bull from the Chocktaws, Cherokee, Shawnees and Creek nations, which speeches I shall send you shortly as there is people going to Illinois soon. The inhabitants of this place is much terrified at the news of the Lake Indians. I think highly necessary for Mr. Kennedy to be continued at this post, as he is well acquainted with the people and no person better fit to deal with them.” (Helm to Clark, Vincennes, 10 April 1779. Missouri Historical Society. Clark Papers, Miami 1779 Records, OVGLEA.)

[33] Helm to Clark, Vincennes, IN, 9 May 1779 in IHC 8: 316-317.

[34] White, The Middle Ground, 384.